Portland Metrozine |

| Second Chance Saturday |

By Eva Hedwig Schueler |

| Rain and Coffee |

By Mehreen Ahmed |

| Packing to Leave Cyprus |

By Lisa Todd |

| Hurry Back |

By Mary Ellen Gambuttil |

| The Bomb |

By Mark Kodama |

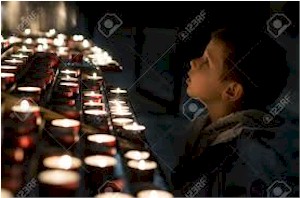

| Candlelight |

By Jim Meirose |

| Gallery Walk |

By Julia Stoops |

| Poetry Suite |

By Fabrice Poussin |

| Stone Wall |

By Norbert Kovacs |

| The Obelisk |

By P.A. O’Neil |

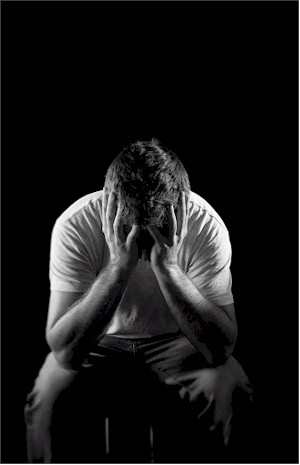

| Slice of Life: Self-Harm |

By Prisoner # 53.3.8.5.7 |

| Spotlight On: Nonviolent Resistance |

By Basha Krasnoff |

|

|

| Short Story Fiction |

Second Chance Saturday By Eva Hedwig Schueler

It is Saturday morning, and you are slouched against the counter in the kitchen, skimming headlines about horrible events all around the world which will have very little impact on you. It is Saturday morning, and the children are crazed with delight. They are rambunctious in that way children inherently know how to be when it is too early in the morning and Mommy and Daddy didn’t get enough sleep, because both of them have been lying awake all night, staring at the ceiling, unable to even turn to the other and acknowledge the shared insomnia. It is Saturday morning, and your wife is making waffles in the waffle iron someone gave you as a wedding present, possibly as a joke. Because it is Saturday morning, and on Saturday mornings you have waffles. It is Saturday, and you are thirty-seven, with a wife, three children under five, a guaranteed tenure and a beautiful brownstone on a quiet street, and it has been three weeks since your wife got out of the hospital after a suicide attempt, which you have not talked about at all. It is Saturday, and you are in the process of rebuilding some kind of life worth living with the woman you love in a world that is going to shit. But you aren’t talking about that, either. It is Saturday, and you continue to be a coward. The baby is in the highchair, whining, reaching fat little arms to your wife. Wanting to be picked up, wanting to be set against the familiar jut of her hip. He is two, and clingy, more so than usual since Mommy went away. But you are ignoring him, because he isn’t full on crying, not yet, and he’s at that age where he needs to learn how to soothe himself. At least, that’s what the parenting book said, which you devoured while your wife was in the hospital. He’ll cheer up when there’s a syrup-drenched waffle in front of him. Your daughters are drinking orange juice at the table, still wearing their pajamas. You can tell they haven’t brushed their hair, but you don’t say anything because it is Saturday. You shuffle toward the cupboard for a coffee cup, paper still in hand as you mentally do this week’s crossword puzzle. Your wife is making the waffles. The water for coffee is boiling, you can hear the kettle shriek, and you should reach for it, but you don’t. You just stand there, pretending to be too busy. Now, isn’t that just the story of your goddamn life? At the blurry edge of your vision, you see your wife half-turn to the stove. She is shushing the baby, sing-song nonsense, reaching for the whistling kettle. The rungs of the burner glow red, angry. She misjudges, reaching too low, grasping at empty air for the handle of the kettle. Her fingers settle on the burner, her palm flattening down against it. Like how she puts her hand on the girls’ backs when guiding them across the street.

She is left-handed, your wife, and wore her wedding ring on that hand for the first year of your marriage, until a sweltering summer pregnancy caused her hands to swell up, and a winter spell of postpartum depression stripped her to skin-and-bone. Now she wears her rings, both wedding and engagement, on a fine silver chain around her neck, sapphires and opals set in bands of white gold, because neither of you support the diamond industry, and none of that matters. Your wife’s hand is burning. You move to your wife, pull her hand away from the burner. You say her name, loudly, as she stares at you with blank eyes. Slowly, her gaze drops to her hand, to where the skin across her palm is blistering into puffy white crescent moons. You watch the realization hit, watch as the pain builds, unbearable in the fraction of a second. Your wife jerks away from you, tries to, struggles in your grasp. A waffle is burning. The kettle, still shrieking, is knocked to the floor, where it bounces and rolls, leaving in its wake a long drag of scalded linoleum. A bird hits the window. All this makes your daughters jump, eyes wide with terror. All this scares the baby; now he is crying in earnest. You grab the kettle, stepping around the new melted gash on the floor. You turn off the stove, set the kettle on the furthest burner, unplug the waffle iron. You guide your wife to the sink, turn on the cold water. Not full blast, just a trickle. Because that faucet on full blast will worsen the hurt of the burn. You try to ignore that the fire alarm is going off. You put your wife’s hand under the cold water. You don’t let her pull away. The baby is screaming, “Mommy, Mommy!” Red-faced and out of breath. You try to ignore that, too. He is two, and has separation anxiety, sparked, no doubt, by your sporadic presence during the first year of his life, and exacerbated by your wife’s recent absence. This baby, which both you and she know full well was a last-ditch effort to bring your attention home and keep it there. Ignore the baby, like you have for the past two years and nine months.

“It’s okay,” your wife says, not loud enough for the baby to hear. She is, she must be, talking to you. “It’s okay. I’m sorry.” I’m sorry, you said, voice cracking with shame as you told your wife about the affair. It’s okay, your wife said, stirring artificial sweetener into her coffee without meeting your eye. I’m sorry, your wife said, woozy from the bottle of sleeping pills she’s swallowed. It’s okay, you said, over and over as you stroked her cheek, pinched her arm, and forced her to vomit into the sink. Anything to keep her awake until the ambulance arrived. Your wife says, “I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to. It was a mistake.” It always is, in hindsight, isn’t it? She pulls away from you, turns off the water. She goes to the highchair, picks up the baby. He throws pudgy arms around her neck, smearing snot on her shirt. The girls, crying now, too, cling to her legs, as if trying to keep her there. Because their world these days is that Mommy is sad, and Mommy could leave at any moment. Because they understand it used to be Daddy that came and went without warning, and now Mommy does, too. You go to turn off the fire alarm, and in the quiet hall, you realize how much of this is your fault. You’re known that for a while, of course, you’re no idiot, but here in this moment, you feel the full weight of what you’ve done. You realize, again, that you are a coward. Realize now, as you never have before, that being a coward almost cost you everything. Realize you have tenure and a brownstone on a quiet street, all the trappings of the good life you wanted to give the children you always planned on having. Realize you have a second chance at this good life you almost ruined. Almost. Just like your wife almost died. Almost. You go to the freezer, fill a dish towel with ice. The baby’s crying subsides into hiccups as your wife bounces him gently in her arms. You hand the dish towel to your wife, smile down at the girls. You propose going out for breakfast at a nearby cafe you always thought your daughters liked. Their dubious expressions tell you that you have gotten this wrong, but that’s how second chances work. You have to fumble and make a fool of yourself, get it wrong when you’re trying to get it right, before you can actually get it right.

You resolve to once again start wearing yours.

|

|

|

| Flash Fiction |

Rain and Coffee By Mehreen Ahmed

As a lightning crackled, Claudia drew the curtains apart. She stood before the long French windows of her penthouse apartment and looked down at a wet alley. The cobblestones of the boulevard shone in the falling rain of dismal clouds. It hadn’t rained for days. She yawned and then she stretched. Across the boulevard, a boulangerie just opened for the day. She saw a young Baker bringing out a basket of fresh croissants. He displayed them in a glassed cove. They were enticing, particularly today, the morning’s gloom added an extra pizzazz to the atmosphere.

A flower shop stood next door. Wet flowers drooped in the heavy battering of the rain. Flowers rooted to their pots’ black soils. A cluster of pots under the shop’s white awning. A young flower girl rushed outside to take the pots indoors. She carried them, one pot at a time. She flitted in and out in a long, pink skirt and a mauve blouse. When she came back to collect more pots, her foot stumbled in her skirt’s hem; she slipped and fell down on her ankle on the wet cobbles. This caught the young Baker’s attention. He ran over to assist the girl and found out that she had a sprained ankle. Claudia watched in earnest. The Baker picked her up and brought her over into his boulangerie. He brought her a glass of water and some pills, which she took. Then he made her the finest cup of coffee, Claudia imagined, and one for himself as well. They sat down under the soaking awning to have their coffee. It was like a Charlie Chaplin silent movie. Claudia fast-paced the events into quick rag-doll movements; Charlie wooing his girlfriend, standing up and then sitting down closely next to her; his arms angled around her neck. She didn’t seem to mind. Then he brought his head down to her lips. She pouted her lips towards his. They kissed. Claudia watched this exciting moment of joy. They kissed and then they laughed. There was not a care in the world. The rain had not abated. Water gushed down the storm water drain in the rivulet.

She trod across her apartment floor, away from the windows towards an umbrella stand set along a brick wall. She picked up a transparent umbrella and set off. She ran down several flights of stairs and out into the open on the pavement across the alley. She stood here under her umbrella and heard the soft swishes of the wind blow. She saw the rain’s tiny drizzles on her umbrella’s downturned dome. There they were, lying idle in each other’s gentle embrace; they wooed, and they cooed, and they whispered delightful sweet nothings without a miss. The rain must go on. It was the rain that held the enigma of the moment. She must make the rain remain longer somehow. She stood there, yes Claudia, stood like the great giant Thor, her umbrella, her hammer in the Nordic god’s immortal grip. Something happened. Her thoughts collapsed like the switching off of a hologram projector. Claudia stepped out of character. No, it was she, who wanted to be the girl in the Baker’s arms. But not in the present, at a different time. She fell through a slit. She was with him, the Baker in Louis’ castle in Versailles. She wanted him all to herself. No, no, wait. There was a revolution. The Baker was taken prisoner from their cottage. He never returned.

Claudia with her umbrella, Miss Havisham’s memories from her dark days, the ghosts, a teasing thin wall of separation between her reality and this. The couple walked on. She watched them promenade and yearned for what was lost. On timeline's linear path, many nonlinear moments played out. The rain tapped away on the cobbles, the boulangerie, and the flower shop, a whiff in the wind of dust and sand. Music of a silent heart, a violin stringed to "Che Sera, Sera. Whatever will be will be," Claudia’s apparition was frozen in time; this long, indelible shadow of the bleak house birdlime.

|

|

|

| Creative Nonfiction |

Packing to Leave Cyprus By Lisa Todd

The end of a school year: a whistleblower’s guide After Jack is fired for rifling through the headmistress’ desk, he returns to the United States while you remain in Cyprus to finish the year. You're determined to prove to the headmistress that you, not she, will win the battle of wills.

Move off campus

Buy a planner

Enlist help

Help clean out the dormitories

Injured

Graduation

The Headmistress

Pack your bags

The cats leave, too

Departing the island

|

|

|

||||

| Creative Nonfiction | ||||

Hurry Back By Mary Ellen Gambuttii

I chose the photographs randomly from the wealth available: she with her young-looking parents when she received her Bachelor of Science in Nursing in New York City; she with my dad in the eighties; a portrait of my nana in her garden when she was close to mom’s age; and my daughter’s boys, at ages five and ten. Now twelve and seventeen, they live in Chicago, and she last saw them six years ago before she came here. My wish has been that she’d find comfort and security in assisted living, and now nursing care, even a measure of contentment. I’ve rarely observed the latter. A gold papered cardboard stationery box in her bottom dresser drawer holds antique photos. Sitting beside her I bend to my right, reach a foot or two to open the drawer, retrieve the box, and place it in front of her. Few words are needed to direct a simple activity we’ve repeated many times. I lift the lid and take out half the stack of photos. Each time we do this, she holds the black and white images more closely to her face; she struggles to name the shadowy blurs from her family history and to describe faded scenes from farm and city—profiles of long lost friends and places—memories from close to a century ago. Mom’s paternal grandparents immigrated to Ellis Island from Austria Hungary at the turn of the 20th century, to homestead in central Pennsylvania where they built a palatial log home, raised many children, and worked a dairy farm. In a studio portrait taken several years prior to my mom’s birth in 1922, their brood of fourteen stands in rows in their Sunday best, mother and father seated at the front. She first points to her father, Michael, but can’t identify the babe in arms, and the two at her grandmother’s knee. Each year, the young women and men; the aunts and uncles she spent time with as a girl, become less familiar to her. In the next set of photos, she slumps on a sweltering Lower East Side stoop or poses on a tenement rooftop with Vincent and a scraggly dog whose name she has forgotten. She almost exclaims at the one in which, at seven, she is framed by Washington Square Park’s Triumphal Arch. Right hand on her hip, she wears a shirtwaist and Mary Janes, and squints at the camera under Buster Brown bangs. Her one and only doll, a gift from the wife of her dad’s new employer, wears a gold velour coat and white fur-trimmed hat. Mom reveals in story fragments a sentimental longing for her rustic birthplace. In Welsh, “Hireath” is a longed-for, yet unattainable place of heart; a spirit place, without want, where much love is supplied. Within that peaceful place of memory, reside her momma, daddy, aunts, and uncles. Her memory of a family’s servile work with little return is diminished, and there is no hunger, want, or illness—a dream without sadness. I know a place like that in my own bones; my own Welsh heritage, and a longing for home where there is a mother, kin, and warmth. Emotions swirl through the stale sensations of her room. The conditioned air is chilled despite my good intentions; my attempts to engage a woman who never easily made connections. I’m one of few left in her life, yet, after sixty-seven years, she finds it hard to reach out to me; or anyone, and she asks nothing of the very one who gives her all I can. ▀ ▀ ▀

She was a nurse who became the wife of an Air Force man. I was their adopted infant girl and fulfilled their immediate needs. A dutiful mother, fastidious in her care, she sewed for me, as her mother had for her, braided my hair, and kept a clean, comfortable home wherever the military located us. I was raised in a disciplined household, had all the quality schools, piano lessons, gifts under the Christmas tree. What my parents wanted from me was that I would be like them. I failed at that; it seems. She told me when I was still in grade school, she had feared the adoption agency might remove me from my new home if she didn’t meet their mothering standards. Maybe that explains her wary, suspicious nature, even her jealousy, or perhaps these traits had been passed on to her. She told me I would never be happy; said she didn’t know or understand me. Did she stop short of expressing distaste for mothering a child not her own by birth; her regrets, resentment? ▀ ▀ ▀ She's vulnerable and knows I see she is, which makes it all the harder for her. And it’s hard for me that I can do little more than what I’ve already done. When my dad died fifteen years ago, I sold their California home of twenty-seven years, and made a home for her near me in Pennsylvania. After my stroke, when she showed signs of needing more help, I encouraged her to enter assisted living. As I regained strength, I helped her through the transition, and continue to support her health care decisions. Yet, at times, I see a weak link in her trust, and that her resentment remains. The staff assures me she doesn’t mean it when she says things like, “You’re not my real daughter,” or when she tells me to leave; that she doesn’t want me with her, I don’t retort like I used to. When unfiltered, she rages at me or the staff, I walk away or return to my new home in Florida. I should stop the unsolicited help. It makes her uneasy, and I exhaust myself when I try too much. We’re both reminded of our family connection when I keep her supplied with necessities and luxuries. Except for Lifesavers, she doesn’t look for anything from me--not the special shampoos, body lotions, or new clothes—but she does enjoy them, and I still cling to my need to nurture. I’ve crossed the line when she’s reminded, I’m not her own; not the child she couldn’t have. ▀ ▀ ▀ It’s October. At ninety-seven she understands that she is in end-of-life care—Hospice. In our separate ways, we struggle with the shortness of time. And I must remove myself now, as she tries to separate from me—from the earth. I understand separation well—I’ve lived with it from birth—and so do you, dear mother who raised me; you suffered when dad was away, as he often was. I felt the sting of your loneliness. I heard the sadness in your voice as you washed the supper dishes and wistfully sighed, “hurry back” while Dean Martin crooned “Return to Me” on the radio. (“Return to Me” performed by Dean Martin. Lyrics by Carmen Lombardo ©1958.)

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

|

| Metrozine Gallery |

Gallery Walk By Julia Stoops |

|

|

| Fiction |

Stone Wall By Norbert Kovacs

To screen out the other people, the elders built the wall at the corner of our land. "Those folks are a danger to us," the old men said, as they set the miles of stone. "All strange to know." The elders meant no one to know them: they piled the stone thirty feet high as if to dwarf the possibility of looking over it at anyone. Our families discouraged us from getting near the place. Still, we children when playing were drawn to the giant structure. Alongside it, we marched, heads high, like soldiers at a fort. One of us once took a loose rock from its exterior and came careering at the rest, his face a mock snarl. "Run, I am ready to kill," he said. "I come from behind the wall." We ran as bid, laughing and screaming by turns. For all our fun over it, we respected the wall; we never made the stones fall or marked them with graffiti. The rampart gave us the reason for our play, after all.

As I thought along these lines, I heard a rustle behind the part of the wall nearest me. The place had been quiet, so it set me to wondering. Now, the wall was that many loose stones stacked up high to about a meter wide. Small holes were all over its front, going clear through to the other side (the elders had built in haste against outsiders rather than for perfection). I decided to look through one of these holes and try to spot the thing I had heard moving. I put my eye to a hole but drew back on the instant. Through the hole, I had seen another person's eye looking back. Who on earth was that? I asked myself. And why had the person been peering onto my side? I recalled what I'd heard of the people living behind the wall and began to form opinions. Maybe he meant some harm. Maybe he was a saboteur. My worry grew over the possibilities. However, I thought to give another look to be sure I had the person right: no use getting excited otherwise. I looked and again saw the eye turned on me. I studied it now and came to feel whoever was looking boded no harm. The dark eye held steady and open, not crinkled by judgment. Still, it was strange to see through that huge wall of all places. The person on the other side spoke to me in short order; I heard him clearly through the gaps in the stone. "Hello!" he said. "Hello," I told him. "You're the first other person to come by this wall, I think." "There have been others." "You've been here before?" "When younger. And you?" "I have been here." The two of us paused. I doubted whether I should speak further with the stranger. It seemed more comfortable to quit. "An out-of-the-way spot for a wall," he said, picking up the thread for us. "Not like your city center." "Yes, it's not too crowded." "I've come sometimes just to be alone here. It was not for all this stone." "I used to come by myself. But sometimes with friends, too." We paused again. The other person lifted his hand and pointed at the hunks of basalt above and below his eye. "Wall makes it strange for two people like us to talk. I mean through these holes." I couldn't figure if I should be encouraging. "Feels strange," I said. "Sort of." The stranger pressed on. "You seem the considerate type. I think we might get along if we really tried to know each other." He added, "It might be easier to on top." "Top?" "Of the wall. If we climbed up there, we could talk face to face. Most people do when they talk in person." It had been only eye to eye between us thus far. His idea to go up struck me as outlandish. "Isn't that asking a lot to climb this?" I said. "A person could get cut on these stones. One or both of us could fall." Then I added my worst fear. "People might come and object that we're together there." "I wouldn't worry over it. If someone did come, I don't think they'd go and kick us off the top for spite. Besides, we might have an easier time scaling this thing than you think. So why not if we are interested to know each other?" Without more hesitation, he started to climb his side of the wall. I saw his hands and feet work into the holes among the stones and ascend, stretch by stretch. Now that we had been talking, I thought it would not be too polite to linger on the ground (though I wished it) while the man took his way upward. With reluctance, I climbed after him. I clamored up the stones and holes, narrowing the distance between us. However, I worried about meeting him the whole way. Who exactly, I asked myself, was this stranger I am going to see atop a thirty-foot wall? He presented some concrete risk. After all, everyone at home insisted his people were a problem. "They're a danger to us," the elders said. My fear of the stranger rose such that I stopped climbing. I clung to mid-wall, hands and feet fixed to the stone. Soon, I felt the strain of holding there and was glad, for it gave an excuse I believed I needed. I called through the wall to the stranger: "I can't go on. This climb is proving too much." Then feeling how that might disappoint him, I added, "Go up top to see if you really like." I heard the other person stop moving. Drawing in his breath, he said, "Okay then." He continued up the wall but more slowly than earlier. Feeling relieved, I descended. It was a hard climb down and once I reached the bottom, uninjured, I was exhausted. That guy must be having a tougher time the longer he goes, I told myself. Maybe he will realize the climb not worth the trouble he's giving it. He can't feel his cause that strongly. But I wasn't sure as I remembered the optimism in his voice. I considered his hints of good humor, too. I looked toward the top of the wall and waited to see if he would appear there.

"Well?" the man called down, an edge of hope in his word. I figured he expected me to make some decision. Well what? I wondered. It seemed odd the man would believe I should know. But as I saw him study me patiently from above, I realized he meant whether he should come down the wall to where I was. The idea felt a surprise to consider. Yes, I told myself, he was still a stranger to me. But I appreciated by now his endeavor in coming after I had quit climbing up to him. He thought that much of trying to meet and know one another even after discouragement. I decided he must mean well. "Come down!" I called, waving for him. The man turned without hesitation and started onto my side. He descended, his face to the stone, his legs placed with care in the gaps. I knew this was how to maneuver on the wall after my own climb, but I became aware in watching him that actually he brooked many dangers in coming. Several stones the man seized offered little for a grip; they were just slick, ugly bumps sticking out into space. He put his hands and feet in gaps that were narrow, small, not suited for steps, many about to cave when touched. It made me nervous to see and worse when I knew he was coming for my sake. In a way, I felt ashamed to watch him risk all this while I waited and did nothing below. Guilt moved me at last. I raised my voice as I saw him about to take too narrow a foothold. "More to the left may be better." He shifted. Moments later, he passed downward, and his hand reached for a loose stone. "Looks firmer one down," I cried. He heeded me; he moved his hand and leg. "Got it!" he called, and I was reassured. With careful work, he descended, and I remained vigilant, stretch by stretch that he took. The wall presented one treachery after another to a climber, and I felt always his next step might mean his end.

|

|

|

| Fiction |

The Obelisk By P.A. O’Neil “Shush! They’ll hear us.” Wallace looked hard at his companion; his face half hidden by the shadow from the corner of the building they were hiding behind. The pale glow from the streetlamp was the only light on this moonless night. Rawls stifled a snicker and took a deep breath as he tried to collect himself. “Sorry, dude, I get the giggles when I’m nervous.” “Rawls, you said you wanted to be part of this. If you can’t control your nerves, take your tools and get back to the dorms before they miss us.” “It’s after two, the Prefect has surely gone to bed by now,” Rawls reminded. “I said I wanted in on this, Wallace, and I meant it. I’ll keep myself together.” “Good, you’d better.” Wallace checked his watch for what seemed like the umpteenth time since they had crept up the edge of the building facing the park where The Obelisk stood. From the corner of his eye, a black streak whirled past and into the street. Wallace fell back off balance, barely catching himself before his back hit the ground, “Geez!” “Easy dude, it’s just a cat,” Rawls snickered under his breath. “Who’s nervous now?” But Wallace ignored the dig from his associate as he played over in his mind the plan that they had discussed every day for the past week. They would dress all in black and camouflage to blend in with the night. Each would carry a set of tools, so if they were split up the other could finish the job. His thighs were heavy with the weight of the twelve-inch iron crowbar and the multi-head screwdriver he had in the pockets of his cargo pants. They hadn’t bothered to bring flashlights. Wallace had walked the route every day since they decided to do this thing. He memorized the path from his dorm, through the adjacent woods, to the street bordering his college campus. Rawls accompanied him on two occasions, both times in the daylight hours. They had portrayed, for anyone who cared, carefree college students making their way through the city park to the convenience store or the local pub. It was one of these visits to the park with Rawls, when they bothered to take a good, long look at what had come to be known as The Obelisk. Some people would stop to look at it, maybe even circle it to look for a plaque, but most just came to see it, or rather not see it, as just another decoration in the park. It was at least twelve-feet tall, four-sided, black plexiglass, wider at the bottom with a slight taper to the flat top. “You sure that Mikki is gonna make it here with the ladder?” Rawls asked as he too remembered the plan. “Yeah, I’ve preprogrammed my phone to give him a buzz when we know the coast is clear,” confirmed Wallace. “Look, there go the cops now.” They pulled themselves back into the shadows as he pressed the send button on his phone. “C’mon, we’ve got twenty minutes until they come back this way.” Each was cautious as they stood up and trotted across the street to the big glass-like structure, the light of the streetlamps shining on the smooth black surface, reflecting onto the concrete walkway before it. They had reached the walkway when a small pickup truck pulled up alongside the park. A man, also dressed in black, got out of the driver’s side of the still running vehicle, to pull an eight-foot ladder from the bed. He spoke not a word as he delivered it to the others. Wallace met him to help carry it the last few feet to the obelisk. With surgical precision, they set up the ladder next to one of the corners of the large black object. Wallace nodded his head, “Thanks, Mikki, I’ll call when we’re done.” Mikki just nodded in return before he wordlessly trotted back to his truck and drove away to wait for the next signal. All the while, Rawls had been kneeling next the structure as he worked with his screwdriver to remove the screws on the lower end of one seam. The truck had barely left curbside as Wallace climbed the ladder, and taking out his own screwdriver, began to remove the screws on the upper portion of the seam. Rawls grunted as he started with each new screw, “These babies are tough – but once you get them started – they come right out.” He slipped another screw free, placing on the ground around his feet. Wallace had climbed the ladder to a height even with his friend’s face if he were standing, “Shhh, boy you have a loud whisper,” he reprimanded, keeping his own voice low. He never looked down while he worked the next screw free, “We’re lucky the city keeps this thing pretty clean, no rust to have to fight with.” Every screw he removed he placed on the painter’s shelf of the ladder and hoped it wouldn’t fall. As he worked each screw free, he thought back to the first time he had learned of The Obelisk. It was during the New Student Orientation tour of the town which hosted his university. He remembered he had also met Mikki and Rawls during that tour, so in a way he felt it was fitting they were involved in a mission to reveal what was hidden behind the shiny black plastic plating. Rawls must’ve had similar thoughts as he shifted to an adjacent corner to remove the screws there. “Remember when you asked the tour guide what was inside of this thing?” He must’ve taken to heart Wallace’s warning about the tenor of his voice, because he worked hard to make sure his words came out in a hushed tone. Wallace had finished removing the last screw and was starting his descent, “Yeah, remember how confused she looked? It was like no one had ever asked before.” He placed his last foot on the ground and grabbed up the A-shaped ladder by the legs to gently lift it around where his partner was working. It was awkward and made a slight dragging sound, “Rawls, can you stop a moment and help me move this thing?” “Yeah sure, man.” He put down his screwdriver and quietly got up to face Wallace on the opposing side of the ladder. They both lifted but, without coordinating their strength, it lifted higher on Rawls’s end and some of the screws fell off the paint shelf onto the concrete at their feet. Horror struck, they both stopped in their tracks, Wallace looked like there had been an explosion, and Rawls expected one from the top of Wallace’s head. The screws bounced and rolled into the grass, and with the silence of the night, it sounded to them more like pots and pans had been dropped, as opposed the diminutive clink of the tiny metal hitting the ground. They stared at each other, waiting for something that wasn’t going to come, but when they realized they were still the only people on the empty street, they both sighed and continued to relocate the ladder. Wordlessly, Wallace climbed back up to start his task. They had lost time, he thought, so he picked up the pace to finish well before the expected return of the police making their rounds. To each it felt like an eternity, but really it had been less than ten minutes, and soon the men were finished with dismantling the one wall of the encasement. Rawls’s gave a wide smile as he stood waiting for Wallace to climb down. Without having to give instruction, they each took their sides of the ladder, and this time, gently moved it out of the way. Wallace felt lightheaded as he realized his goal of revealing the secret of The Obelisk was at hand. He stood on the left and Rawls on the right. The illumination from the streetlamps was bright enough Wallace could see his face in the shiny black surface, his smile broad and his eyes bright. “This is it,” he thought, “three years of waiting, over in an instant.” He raised his crowbar and began to pry between the now unsecured sheets of plexiglass. Rawls did the same on his side. He wedged the splayed end of the tool in the small crack and applied pressure at about a foot up from the ground. He worked it until the sheet gave way, no longer connected to anything. Moving about eight inches upward, he would repeat the action, each time the plastic pulling a little further and further from the stationary wall it was once attached to. As he worked his way up, Rawls began to giggle. Wallace wanted to stop him, but the thrill of opening this sarcophagus to reveal something unimaginable had overwhelmed him as well. Finally, with a crack, the plumber’s putty which had been used for waterproofing the seam broke loose. The hands of the two men were the only thing supporting the free panel. “We’re gonna bring it down, aren’t we?” asked Rawls, giddy with exhilaration. “Yeah, but first I must call Mikki, he needs to see this too, you know.” Wallace freed one of his hands to reach into a pocket, pull out his phone, and like before, wordlessly signal his other friend to join them. He replaced his phone and put his other hand back into a position which would allow him to ease down the panel. He looked at Rawls, nodded twice, and together they started to lower the sheet of plexiglass. Slowly, the sheet pivoted on its base as the men walked backwards allowing it to fall forward towards the street. It was heavier than they had imagined. Mikki’s truck arrived in time for him to jump out to help his friends place it on the ground. The three men looked at each other with congratulatory smiles. They approached their open treasure chest with a quiet reverence to surveil their prize. The light from the street did not penetrate far into the darkness. Mikki pulled a small flashlight from his pocket and shone it onto the still figure which had been encased for who knows how long. “It’s a statue,” Rawls exclaimed. “A statue of an old man in a funny uniform. Look at his sword, and those weird gloves.” “I think they called that a sabre,” corrected Mikki. “Yeah, but of who is he?” Wallace asked, not knowing whether he should be disappointed. “Here, Mikki, shine the light on the base.” Mikki had been surveying the concrete statue with his torch from the top to the base, but finally rested it upon a bronze plaque placed below the man’s booted feet. The three men leaned in to read, In memory of the valiant soldiers of the Confederacy. “Confederacy? What’s that?” Mikki asked. “I don’t know, but it’s important enough that someone thought to place a tribute to it,” answered Wallace in a solemn tone. Rawls had been scratching his head as he tried to make sense of the dedication, “I know, Confederacy, do you think they might’ve meant confederate?” The other men looked at him with a ponderance, could Rawls have solved the puzzle of the meaning of the plaque? “Think about it,” he continued, “doesn’t confederate mean bad, like in confederate money?” Wallace’s mouth dropped open, he tried to speak, but there were no words adequate to criticize his friend’s misbegotten logic. “That’s counterfeit money, stupid,” chided Mikki. “Either way, I figure we’ve been out here way too long.” Wallace snapped out of his fugue, “Mikki’s right, we can figure this out later C’mon, help me with the ladder.” Mikki turned off his flashlight and ran back towards his still running truck. Rawls pushed up the paint shelf of the ladder as Wallace collapsed it, then the two carried it to the curb where they placed it in the bed before they hopped in themselves. As Mikki drove off, Wallace looked back at the now exposed statue, the plexiglass front still lying before it on the ground, a collection of screws scattered about. He knew he had to research the meaning of the plaque or tonight’s events would just be chalked up to a juvenile college prank. ▀ ▀ ▀ It was barely after sunrise the next morning when two men in coveralls stood in much the same way the trio had before the now exposed contents of The Obelisk. Patches on their backs read Department of Public Works. The younger of the men just stared at the statue while the other started looking down at the grass around the supine plexiglass sheet. “Do you think we’ll be able to find all of the screws?” he asked. “Why would anybody do this? I mean, deface a public monument like this?” his companion asked as he turned away from the concrete man towards the one of flesh and bone. Getting down on his hands and knees to pick screws out of the grass he responded without looking up, “I don’t know, it happens every decade or so. I don’t understand why the city doesn’t just take it down.” “Every decade or so, how long has it been here?” “I don’t know really. The Obelisk has been here as long as I can remember.” The older man stopped his exploration long enough to take a long look at the concrete soldier, and sighed, “C’mon, help me get this glass up. I think I have enough screws to at least keep it upright until we can replace the others.” Both men squatted down on either side to lift the black sheet, tilting it upward, a reversal of the way it had come down. Once in place, they each took some screws, fit them place, and secured it enough for them to let go, sure the sheet would not fall back to the ground. The older man started walking back to the city truck parked at the curb. “That should hold it until we get some plumbers putty and some more screws.” He had reached the side of the truck before he noticed his coworker had not followed and was still looking at The Obelisk as if he could see the statue through the black plastic walls. “You comin’ or are you just going to stand there all day?” His companion joined him at the side of the truck before he asked the question which had burned in his mind since he arrived at the park, “Yeah, but why would the city make a monument to this soldier and then decide to box him up?” The older worker turned once more towards the monument, shrugged his shoulders, and then turned back to his truck shaking his head, but as he opened the door to get in said, “Hell if I know, politicians!”

|

|

|

| Personal Essay |

Slice of Life: Self-Harm By Prisoner # 53.3.8.5.7 “The community’s best and brightest,” I think as I drop to the floor and slide halfway under the bunk, straining until I’m finally able to grab a small container stuck to the bottom of the bunk with magnets. Hopping up, I quickly pad back to the window, heart slowing ever so slightly when I see the puddle of drool. Still good. I grab my razor on the way back to my bed and sit down, setting the container on the bed next to me. Bringing my right ankle to my left knee I study the dust motes floating in the sunlight. The razor twirls in my fingertips. I’ve never personally been into self-harm, so my mind branches down the road after road that led here, wondering how this might be. I shave a section of my calf bare and thoroughly apply a layer of deodorant, just like that one old-timer told me to. Dumping out the contents of the container next to me, I pick up a piece of transfer paper and press the design I drew for myself the day before. As I do, I pick up the tattoo gun and do a quick visual check, then begin shaking the ink. All is ready. Sorry mom.

|

|

|

| Personal Essay |

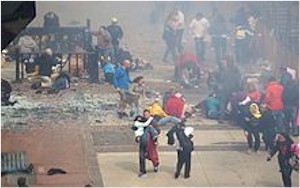

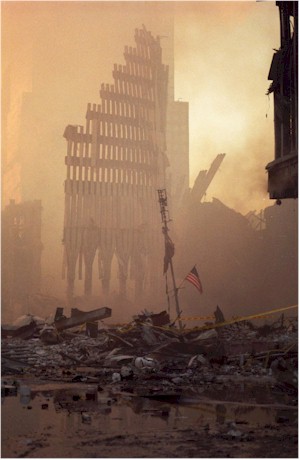

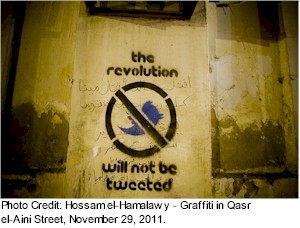

Spotlight On: The Lasting Power of Nonviolent Resistance By Basha Krasnoff A seismic shift is occurring within our society during the year 2020. Not only are we fighting a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic and navigating a surreal political landscape, we are turning the tide against systemic racism. The Largest Civil Rights Movement in U.S. History

Since May 26th, there have been more than 4,700 demonstrations, for an average of 140 per day; and, dozens to tens of thousands of protesters have joined together in about 2,500 small towns and large cities. This geographic spread of protests has signaled the depth and breadth of the movement’s support (1). And the crowd counts are of extraordinary scale. Protests peaked when half a million people turned out at 550 sites on a single day in June during more than a month of protests across the United States. On June 6th, at least 50,000- 80,000 people turned out at Philadelphia’s Independence Mall; 20,000 at Chicago’s Union Park; and up to 10,000 on the Golden Gate Bridge were engaged in protests. There have been daily BLM protests in Portland Oregon for 14 straight weeks and t he Portland Police Bureau has declared a riot 18 times since the death of George Floyd. Polls suggest that between 15 million and 26 million people in the United States have participated in demonstrations over the death of George Floyd and others (2). What Makes this Movement Different?The political climate across the country has conditioned us to protest the adversarial stance that the Trump administration has taken on issues like guns, climate change and immigration. In fact, there have been more protests since the start of the Trump administration than under any other presidency since the Cold War. According to the Washington Post, one in five Americans say that they have participated in a protest since the start of the Trump administration—19 percent of whom said they were new to protesting.

In fact, more than 40 percent of counties in the United States—at least 1,360—have had a protest. Unlike past Black Lives Matter protests, nearly 95 percent of the counties that had a protest are majority white and nearly three-quarters of those counties are more than 75 percent white. It would be really hard to overstate the scale of this Movement compared to the Civil Rights Marches during the 1960s—which when added all together, involved hundreds of thousands of protesters, not millions. The reality and significance of generalized white support for the movement in the early 1960s, reveal that relatively few whites were active in the struggle in a sustained way and certainly nothing like the percentages of whites taking part in the Black Lives Matter Movement (3). Also, Black Lives Matter has attracted protesters who are younger and wealthier. The age group with the largest share of protesters is people under 35 and the income group with the largest share of protesters is those earning more than $150,000/year. Half of those who said they protested said that this was their first time getting involved with any form of activism or demonstration. A majority said that they were motivated to protest after watching a video of police violence toward protesters or the Black community within the last year. And of those people, half said that it made them more supportive of the Black Lives Matter movement (4). The protests are colliding with another watershed moment: the country’s most devastating pandemic in modern history. Being home and not able to engage in the busyness of life seems to be amplifying the power that the George Floyd video has had to engage us in protest activity (5). What Has Changed?

It looks, for all the world, like the Nonviolent Resistance Movement in the United States is achieving what very few do: setting in motion a period of significant, sustained, and widespread social and political change. We appear to be experiencing a social change tipping point—which is as rare in a society as it is potentially consequential (7). Efficacy of Nonviolent ResistanceThe best news is that recent research shows that nonviolent civil resistance is far more successful in creating broad-based change than violent campaigns are. And the key elements necessary for a successful nonviolent campaign are in evidence in the United States: ►A large and diverse participation that’s sustained.►A movement that elicits loyalty shifts among security forces and other elites. (There are many different societal pillars that support the status quo. If they can be disrupted or coerced into noncooperation, then that’s a decisive factor.)►Campaigns need to involve more than just protests; there needs to be a lot of variation in the methods they use.►When campaigns are repressed — which is basically inevitable for those calling for major changes — they don’t either descend into chaos or opt for using violence themselves. The most important caveat of the research findings is this: If campaigns allow repression to throw the movement into total disarray or they use it as a pretext to militarize their campaign, they’re essentially co-signing what the regime wants — for the resisters to play on the regime’s own playing field. If the movement descends into violence, it will probably get totally crushed.What Next?In the aggregate, Nonviolent Civil Resistance is by far the most effective campaign for producing change. In fact, a surprisingly small proportion of the population guarantees a successful campaign. Consider that protests to unseat government leadership or for independence typically succeed when they involve as little as 3.5 percent of the population at their peak. In the United States today, that would mean around 11.5 million citizens. Could you imagine if 11.5 million people—that’s about three times the size of the 2017 Women’s March—engaged in mass noncooperation in a sustained way for nine to 18 months? Things would be totally different in this country. The good news is that even when they “fail,” nonviolent civil resistance campaigns still lead to longer-term reforms than violent campaigns do (8). All indicators suggest that if we sustain our current level of nonviolent resistance across this country, the change we are working for, is inevitable. References1. Kenneth Andrews, PhD. (UNC at Chapel Hill). Recommended ReadingChenoweth, Erica and Richard English, Andreas Gofas, and Stathis N. Kalyvas:Civil Resistance: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2019) Chenoweth, Erica and Richard English, Andreas Gofas, and Stathis N. Kalyvas: The Oxford Handbook of Terrorism (Oxford University Press, 2019)

|

|

|

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| Fall 2020 |

|

Mehreen Ahmed is an award-winning writer of novels, novellas, short stories, creative nonfiction, flash fiction, prose poetry, and memoirs; as well as academic papers, essays, and journalistic pieces. Her works have been podcast, anthologized and translated in German, Greek and Bengali. Mehreen’s work has been internationally acclaimed and published in the following: Routledge, Cambridge University Press, (Cambridge Core), University of Hawaii University Press, Michigan State University Press, ISTE, Callej.org. Journal, University of Kent, Canterbury Press, The Sheaf, University of Sackachewan Press. The Bombay Review, Breaking Rules Publishing: The Scribe Magazine, FlashBack Fiction, Scars Publications: Down in the Dirt Magazine and cc& d magazine, Portland Metrozine, Ellipsis Zine, Ginosko Literary Journal, The Cabinet of Heed, Straylight Magazine, Creativity Webzine, Mojave Heart Review, The Piker Press, Kitaab International, Nthanda Review, CommuterLit.Com, Academy of the Heart and Mind, Adelaide Literary Magazine, Scarlet Leaf Review. The World of Myth Magazine, Jumbelbooks, Literary Yard, Fear and Trembling Magazine, Terror House Magazine, Connotation Press, The Punch Magazine, Re:Action Review, Furtive Dalliance Literary Review, Flash Fiction North, Velvet Illusion Literary Magazine, Storyland Literary Review, Spillwords Press, CafeLit Magazine, Story Institute, Cosmic Teapot Publishing, The Sheaf: Campus newspaper for the University of Saskachewan, Clarendon House Publication, Dastaan World Magazine, Books On Demand, Germany, Your Nightmares: Nyctophilia. gr Magazine, Best Poetry: Contemporary poetry online . This piece was previously published in Adelaide Literary Magazine. Magazine No. 37. June Issue (2020). To learn more about Mehreen’s work visit:her page at Amazon. She has MA degrees in English Literature and Linguistics. Mehreen was born and raised in Bangladesh and currently lives in Australia. Bengt O. Björklund is a poet, artist, journalist, photographer, writer, musician and editor, born in Stockholm. Between 1968 and 1973, he was imprisoned in Istanbul for possession of $20 worth of hashish. In that Turkish prison, he met an array of international artists, poets and musicians and from that experience, he embarked on an artistic voyage in many directions. Valuable sources of inspiration during those early years were his fellow inmates and friends, the Japanese artist Koji Morrishita and the Italian artist, poet, and Dadaist, Antonio Rasile. The film, “Midnight Express” tells the story of this imprisoned “artist colony” and the character, “Erich” represents Bengt in the film. For almost 50 years Bengt has written poetry both in Swedish and English. Of the ten books of poetry he has published, five are written in English. In 2018, Bengt was awarded the title, “Sweden Beat Poet Laurette" by the National Beat Poetry Foundation Inc. Bengt’s journey as a visual artistic began in Istanbul so many years ago with coloured pencils and watercolour. The first exhibition of his visual artwork was at Joe Banks Gallery in Copenhagen 1975. Since then he has exhibited his art in many international venues. Bengt resides in Sweden with his wife. Mary Ellen Gambutti is a prolific writer of the Japanese poetic forms of Haibun, Haiga, Haiku, Sedoka, and Zuihitzu, lyrical poetry and creative nonfiction in the forms of memoir, slice of life, flash, and vignette. She is a retired horticulturalist and landscape gardener, an adult adoptee in reunion, Air Force daughter, and a hemorrhagic stroke survivor. Her book, Permanent Home: A Memoir, was published in December 2018 and is available at her website. Her work has appeared in Portland Metrozine. “Hurry Back” was previously published in Spillwords in February 2018). She lives in Sarasota, Florida. Mark Kodama is a trial attorney and former newspaper reporter. He is currently working on “Las Vegas Tales,” a work of philosophy, sugar-coated with meter and rhyme and told through stories. More than 150 of his short stories, poems and essays have been published in anthologies, including those published by Black Hare Press, Clarendon Publishing House, Eerie River Publishing, Escaped Ink Press and Devil’s Party Press. His story, "Executioner's Wife" appeared in Portland Metrozine (Spring 2020). Mark lives in Washington, D.C. with his wife and two sons. Norbert Kovacs is a writer of short stories and flash fiction. His interests include hiking in the woods, exploring museums, and reading literary fiction. He has a B.A. in English from Northwestern University. Norbert has published stories in Westview, Thin Air, Hypnopomp, Corvus Review, and The Write Launch. For more information about his publications visit www.norbertkovacs.net. Norbert lives and writes in Harford Connecticut. Basha Krasnoff is the Editor of the Portland Metrozine. She is an accomplished creative writer of poetry, short stories, and nonfiction. Basha's professional career spans academic, expository, journalistic, narrative, research, and technical writing. She has written museum and gallery catalogues for visual artists and liner notes for musician albums. She has been the editor of six publications including the original print version of this literary journal. She lives and works in Portland, Oregon. Jim Meirose is the author of short and long works of fiction that have appeared in numerous publications, including South Carolina Review, New Orleans Review, Xavier Review, Witness, Into the Void, Exterminating Angel, Phoebe, Otoliths, Baltimore Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, American Literary Review, 14 Hills, and many others. H is published novels include No and Maybe - Maybe and No (Pski's Porch). Le Overgivers au Club de la Résurrection (Mannequin Haus), Understanding Franklin Thompson (JEF pubs), and Sunday Dinner with Father Dwyer (Optional books). For further information visit his website or @jwmeirose. Jim lives in Somerville, New Jersey. P.A. O’Neil is a writer whosestories have been featured internationally in more than thirty publications, including multiple anthologies and on-line magazines and journals. One of her stories has been nominated for “Story of the Year” on the Spillwords Press website. Her collection of short stories, Witness Testimony and Other Tales, was recently published. Links her collection of short stories as well as to publications that feature her work, may be found under the photo sections of her Facebook author page, P.A. O’Neil, Storyteller or her Amazon author page, P.A. O’Neil. Her work has appeared in Portland Metrozine. “The Obelisk” was first published in the October 2018 in Dastaan World Magazine. P.A. resides in Olympia, Washington. Fabrice Poussin is a photographer and the author of novels and poetry. His writing and photography have been published in Kestrel, Symposium, La Pensee Universelle, Paris, and other art and literature magazines in the United States and abroad. His photography has been published in The Front Porch Review, the San Pedro River Review as well as other publications. Poussin teaches French and English at Shorter University and is the advisor for The Chimes, the Shorter University award winning poetry and arts publication. His paintings were featured in the “Gallery Walk” of Portland Metrozine. He lives and works in Rome, Georgia. Prisoner # 53.3.8.5.7 is a pseudonym for a young writer who is currently incarcerated. While serving his sentence, he shares insights into his everyday life as a prisoner refracted through his lens of intelligence, talent, and love. For these purposes, and because he is blessed with an indominable spirit, he identifies himself with this sequence of his lucky numbers. He is confined in Oregon. Eva Hedwig Schueler is a new writer and recent graduate of Columbia College Chicago with a BA in creative nonfiction. Her essay "Headcheese" appeared in t he October 2017 print edition of Punctuate Magazine. Eva Hedwig is currently living in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Julia Stoops has explored process-driven, mixed media work for over 30 years. She is a recipient of Oregon Arts Commission fellowships in both art and literature. Her work has been reviewed Art in America (2014), and she was a Ucross Foundation resident in 2016. Julia is also a writer and her debut novel about a group of environmental/media activists, Parts per Million, was published by Forest Avenue Press in 2018. Born in Samoa to New Zealand parents, Julia spent her childhood in Japan, Australia, New Zealand and Washington, D.C. She has lived and worked in Portland, Oregon since 1994. Lisa Todd is a writer of short fiction and literary memoir. Her work has been published in Oregon Library Association Quarterly, The Manifest-Station, the Oregon English Journal, and the Portland Metrozine. A librarian with a lifelong love of books and information, Lisa lives in Beaverton, Oregon with her husband, daughter, and two cats.

|

|

|

| SUBMISSIONS |

| Fall 2020 |

Buoyed by the thriving literary community of Portland, Oregon, we reach out to the global community to inspire, encourage and broadcast creative expression. Wherever you are on planet Earth, we welcome you to share your vision, your voice, and your point of view! The Portland Metrozine is published quarterly (Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter), but submissions are accepted at any time. We accept simultaneous submissions but please let us know if your work is accepted elsewhere. We will consider previously published work with a citation for the original publisher and date. You can learn more about our community via Facebook. Submission GuidelinesSend an email message to the Editor at: 1. In the body of your email, please include: ■ Title of your submission 2. For document files, use MS Word (.doc, or .docx), or ASCII text (.txt). Attach your document and/or image file(s) according to these guidelines:

Creative Non-fiction: 1 essay per submission (max: 4K words) ■ double-spaced manuscript ■ one-inch margins ■ paginated

|

|

|

| KUDOS Gallery |

| Fall 2020 |